Foundation Series: Strategic Risk

How Financial Services Organizations Can Better Define, Monitor, and Govern Strategic Risk.

Introduction

In today’s fast-changing business environment, senior management and the Board of Directors (“the Board”) face a growing array of uncertainties, e.g.: rapid technological disruption, climate risks, changing customer behaviors, regulatory shifts, and geopolitical volatility. Many of these factors cannot be neatly compartmentalized into traditional risk categories like credit, liquidity, or operational risk. This is where strategic risk enters the conversation.

Despite its increasing relevance, strategic risk is still inconsistently defined across many organizations and is often used as a catch-all for risks that appear significant or high-profile. As such, there is no single universal model for managing strategic risk. Larger Financial Services Organizations (FSOs) often maintain dedicated strategic-risk functions with formal risk and oversight routines, while smaller FSOs may choose to integrate strategic risk considerations into existing processes such as strategic planning, capital planning, recovery and resolution planning, new activity, and enterprise level decision-making. The approach varies with the FSO’s size, complexity, and business model. That variability is both expected and appropriate.

Strategic risk remains an evolving risk category, in part because it has not existed as long, or as explicitly, as traditional disciplines such as credit and market risk. Financial institutions have spent centuries refining the tools, data, and governance structures that underpin those established risk types, but equivalent routines for strategic risk are less mature. Although strategic risk is not a new concept, its prominence has grown substantially as business models, technologies, and external environments have become more complex and fast-moving. As a result, many organizations are still developing their capabilities, measurement approaches, and governance practices needed to manage strategic risk with the same rigor applied to more traditional categories.

Regulators are also not entirely on the same page as it comes to this risk category.

Strategic risk is the risk to current or projected financial condition and resilience arising from adverse business decisions, poor implementation of business decisions, or lack of responsiveness to changes in the banking industry and operating environment. The board and senior management, collectively, are the key decision makers that drive the strategic direction of the bank and establish governance principles. The absence of appropriate governance in the bank’s decision-making process and implementation of decisions can have wide-ranging consequences. The consequences may include missed business opportunities, losses, failure to comply with laws and regulations resulting in civil money penalties (CMP), and unsafe or unsound bank operations that could lead to enforcement actions or inadequate capital.

Whilst the OCC have a specific section on strategic risk and formally recognize it, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and Federal Reserve Board (“the Fed”) stress the importance of “the sustainability of banks’ business models” and “forward-looking risk management” via regulatory guidance, but do not have a clearly distinct categorization of strategic risk. Here, I found comments from Fed Governor Randall S. Kroszner during the 2008 Financial Crisis insightful on this topic:

I have tried to lay out the importance for banking institutions to develop and maintain a strategic risk management framework that fully incorporates all the risks they face--both internal and external--when making choices about what activities and markets in which they will operate. Indeed, having a corporate strategy that does not include risk management at its core is not really a strategy at all. Market infrastructure, which affects not only the ways in which firms are connected to each other but also the types of shocks to confidence that they may encounter, is an important external factor that should be taken into account in strategic risk management.

Essentially, regulators expect institutions to treat strategic risk as a Board and senior-management-level concern, and not a residual afterthought.

Characteristics of Strategic Risk

At its core, strategic risk refers to the threat that an organization will fail to achieve its long-term objectives because its chosen strategy, or the execution of that strategy, proves flawed, or because external events undermine the premises upon which the strategy is based.

Some key characteristics of strategic risk:

Strategic risk deals with forces that really move the needle on revenue and capital.

Because strategic risk is intertwined with the FSO’s long-term business objectives, it inherently has a longer time-horizon than other risk types.

The FSO’s decision-making is captured in the annual refresh of the three- to five-year strategic plan and is therefore a core component of strategic risk.

Strategic risk involves decisions taken (or not taken) by senior management and the Board, including business model design, market positioning, major investments, capital allocation, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), entry/exit decisions.

Strategic risk is as much focused internally, on risks to and from the strategic plan, as externally on market forces, geopolitics, macroeconomics, climate risk, technologic disruption, etc.

Strategic risk management is the disciplined validation of the assumptions that underpin a firm’s strategic choices, recognizing that these assumptions, often taken for granted during strategy design, are frequently the first points of failure when the environment shifts.

Because of these characteristics, strategic risk cannot be effectively managed with the same toolkit as operational or compliance risks (e.g., procedures and internal controls). Rather, it demands strategic judgment, foresight, robust governance, and continuous horizon-scanning.

Strategic Risk as a “Dumping Ground”

Because strategic risk is broad, long-term, and often qualitative, it can become a convenient receptacle for any risk that does not neatly fit into traditional risk categories. Common traps include high-visibility, politically sensitive, or difficult-to-manage projects. As such, consider the following:

Just because a project is high-visibility or cross-cutting does not automatically mean it rises to the level of strategic risk - there must be impact to either the strategic plan / strategic positioning (competitive advantage and market position) or long-term profitability, revenue, and capital.

When risks are lumped under “strategic”, it becomes unclear which governance body, risk function or management level is accountable.

Putting many diverse risks under “strategic” may create the illusion of oversight, while in reality the organization lacks the tailored tools, metrics, and governance to manage them effectively.

Over-classifying risks as strategic can dilute senior management’s focus, resulting in broad but shallow attention rather than the deeper engagement truly strategic issues require.

Shape of Strategic Risk

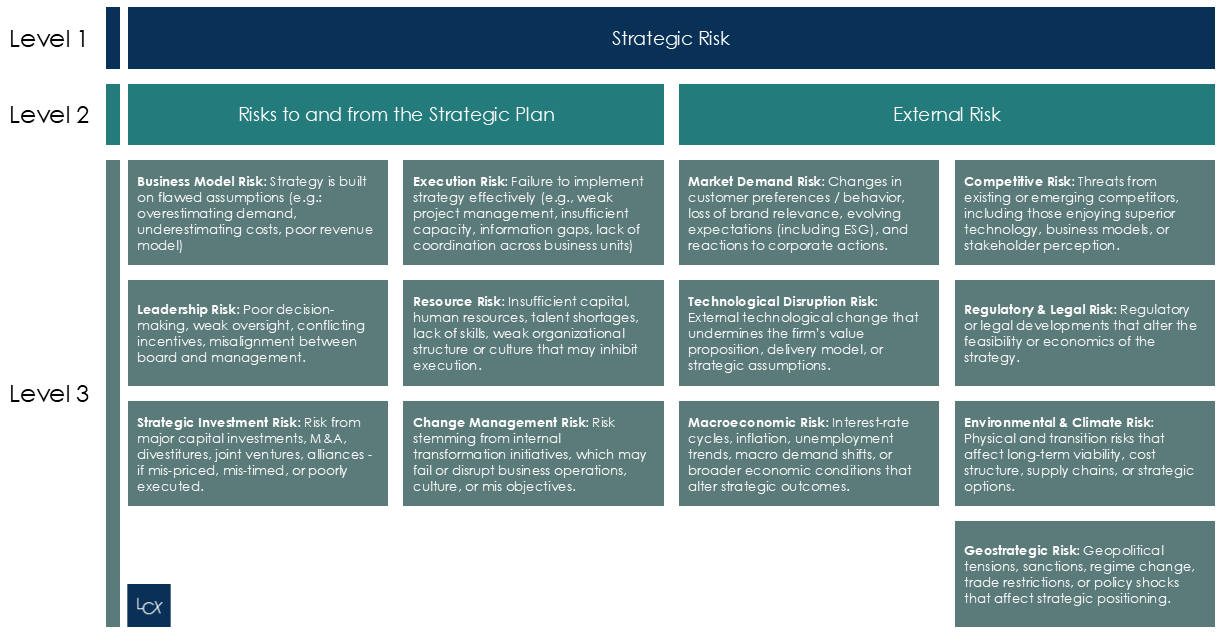

To avoid the dumping ground problem and to sharpen clarity, I propose the following three-level taxonomy. This structure may help senior management and risk teams define, categorize, and govern strategic risk more effectively. See figure 1 below.

Figure 1 breaks Strategic Risk into two main buckets:

Risks to and from the Strategic Plan

Business Model Risk

Execution Risk

Leadership Risk

Resource Risk

Strategic Investment Risk

Change Management Risk

External Risks

Market Demand Risk

Competitive Risk

Technological Disruption Risk

Regulatory & Legal Risk

Macroeconomic Risk

Environmental & Climate Risk

Geostrategic Risk

How this breakdown is helpful in managing strategic risk

By distinguishing between strategic plan risks and external environmental risks, and then breaking those into more granular sub-categories, risk teams and senior management can better prioritize which risks warrant board-level monitoring, which need dedicated mitigation plans, and which can be handled at front-line-unit or operational levels.

Different kinds of strategic risk demand different owners, e.g.:

Front-line-unit leaders for execution risk.

Strategy or corporate function for investment risk.

C-suite and the Board for competitive, market, and regulatory risk.

Risk management or compliance for external threats.

Not all big projects are strategic; not all systemic threats require the same level of oversight. A taxonomy helps avoid overloading senior management with noise while ensuring material risks get sufficient attention.

When strategic risk is clearly defined and structured, risk considerations can be built into strategy formulation, not retrofitted. This supports a culture where strategic risk management is integral to strategic planning — not an afterthought.

Strategic Plan

FSOs engage in a variety of planning activities as part of their governance processes to ensure safety and soundness. Strategic planning forms the high-level roadmap from which other critical planning activities derive, ensuring the FSO has the necessary capabilities (personnel, financial, technological, and organizational) to achieve its goals. Typical planning activities conducted by FSOs:

New Activity (products/services)

Capital

Disaster Recovery / Business Continuity

Recovery & resolution

Operational

Strategic

Now let us unpack the last bullet - Strategic planning:

The FSO’s entire strategic planning process, which defines long-term goals and the strategy for achieving them, is inherently aimed at mitigating strategic risk. The core components of the strategic plan include:

Definition of long-term goals (three to five years)

Description of current state, target state, pathway for achieving target state, and appropriate measurements of progress.

An effective strategic plan must be based on realistic assumptions and be consistent with the FSO’s risk appetite, capital plan, and liquidity requirements.

During this process, the Board must oversee the entire strategic planning process, providing credible challenge to management’s assumptions and recommendations during the planning phase. The Board must also monitor the plan’s implementation and, if the strategy is unreasonable, drive corrective actions or change the strategic direction.

Senior management, in consultation with the Board, develops the strategic planning process. Management is responsible for executing the Board-approved strategic plan, monitoring its implementation, and developing the policies and processes to guide its execution.

The board and senior management must regularly measure progress through scorecards or reports, indicating whether objectives and timelines are being met and if corrective actions are necessary.

The CEO should be responsible for developing a written strategic plan with input from frontline units, Independent Risk Management, and Internal Audit. The Board should evaluate and approve the strategic plan and monitor management’s efforts to implement the strategic plan at least annually. The strategic plan should cover, at a minimum, a three-year period and

contain a comprehensive assessment of risks that have an impact on the covered bank or that could have an impact on the covered bank during the period covered by the strategic plan.

articulate an overall mission statement and strategic objectives for the covered bank, and include an explanation of how the covered bank will achieve those objectives.

explain how the covered bank will update, as necessary, the risk governance framework to account for changes in the covered bank’s risk profile projected under the strategic plan.

be reviewed, updated, and approved, as necessary, due to changes in the covered bank’s risk profile or operating environment that were not contemplated when the strategic plan was developed.

External Risk Landscape

Effective strategic risk management relies not only on the quality of the FSO’s strategic choices but also on the continuous monitoring of the environment in which those choices are executed. Because strategic risk reflects shifts in external forces, organizations must maintain disciplined routines for identifying, measuring, monitoring, controlling, reporting, and escalating threats as they develop.

A core component of this monitoring function is structured environmental scanning. Using the sub-categories in the strategic-risk taxonomy, FSOs should routinely evaluate how external developments may challenge the assumptions embedded in the strategic plan. This scanning should be systematic, evidence-based, and closely tied to the FSO’s current and future strategic priorities.

In parallel, measurement of top, material and emerging strategic risks is essential to managing risk exposure. Tracking changes in the severity, likelihood, or velocity of these risks enables management to understand how external pressures or internal performance trends might alter strategic trajectories. These measurements provide the analytical foundation for determining whether adjustments to strategy, resource allocation, or execution plans are necessary.

Equally important is clear reporting and escalation protocols. Strategic threats identified through monitoring should be reported to senior management and the appropriate risk management committees and escalated to more senior governance bodies all the way up to the Board, as appropriate. This ensures that significant developments receive timely attention and that decision-makers are equipped with the information needed to evaluate potential impacts on the strategic plan.

Ultimately, a disciplined approach to strategic-risk monitoring enables FSOs to detect emerging threats early, assess their implications, and take corrective action before strategic objectives are materially compromised.

Strategic Risk Scenarios

An FSO enters a new line of business (e.g., digital banking) without fully assessing how regulatory changes, competitive dynamics, or technological disruption could affect profitability. If the new line fails, it may impair long-term revenue and capital.

A legacy FSO chain failing to invest early enough in e-commerce or omnichannel retailing as consumer preferences shift - resulting in dramatic loss of market share and obsolescence.

An FSO making a major acquisition to expand into a new market, but misjudging integration challenges, overpaying, or underestimating cultural and operational risks, thereby impairing expected synergies, and damaging long-term value.

Multiple credible studies and supervisory reports find that failures of strategy, poor business models, M&A mistakes, misreading demand or competitive shifts, are a major (often primary) driver of large value losses or institutional failure; however, evidence is heterogeneous in method and sector, and causality is often complex.

Conclusion

As the operating environment becomes more dynamic and uncertain, strategic risk is no longer a peripheral concern but a core component of sound governance. Institutions that define strategic risk clearly, structure it thoughtfully, and monitor it rigorously are better positioned to adapt, allocate resources wisely, and make resilient long-term decisions. By embedding strategic risk thinking into planning, oversight, and execution, FSOs strengthen not only their strategies but their capacity to navigate an increasingly complex future.