Foundation Series: Risk Management Life Cycle

A deep dive into the Risk Management Life Cycle - how Financial Services Organizations (FSOs) identify, measure, monitor, respond, and report within a strong governance framework.

What do risk managers do? That is a great question, which often invites fanciful answers such as “predicting the future” - and we all know how easy that is. In reality, effective risk management is about applying a structured approach. This approach, known as the Risk Management Life Cycle (RMLC), provides a repeatable and principle-based process for identifying, measuring, monitoring, responding, and reporting on risks. It is the continuous mechanism that translates seemingly disparate activities into actionable insight and informed decision-making.

But to truly understand the RMLC it must first be placed within its broader context; risk governance. Risk governance establishes the requirements, roles & responsibilities, and oversight structures that together with the RMLC make it possible to effectively manage risk across the enterprise. It is the governance architecture that connects individual risk management categories and programs to the FSO’s strategic objectives and risk appetite, defining how risk information flows to decision-makers at every level.

“Risk governance is an important element of corporate governance. Risk governance applies the principles of sound corporate governance to the identification, measurement, monitoring, and controlling of risks to help ensure that risk-taking activities are in line with the bank’s strategic objectives and risk appetite. Risk governance is the bank’s approach to risk management and includes the policies, processes, personnel, and control systems that support risk-related decision making.”

RMLC - the Cornerstone of a Principle-Based Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF).

The RMLC is a foundational element of the ERMF and is further codified in applicable policies and procedures, where it is brought to life across risk categories and risk programs. It is inherently adaptable, stemming from its principle-based nature, ensures it can be readily applied to diverse risk and governance routines. This makes the RMLC a crucial and flexible building block that ensures a consistent, disciplined, and comprehensive approach to managing risk.

The Elements of Continuous Risk Management

Risk management is continuous, comprehensive, and ever evolving - in line with the business strategy, the regulatory landscape, and emerging threats. Hence the circular nature to the diagram in figure 1 below.

At a high level, the RMLC enables organizations to:

Articulate current and emerging risks.

Quantify their potential impact and likelihood.

Establish metrics to measure risk exposure.

Implement appropriate risk response.

Communicate clearly with stakeholders and elevate top and material risks to senior leadership, the Board of Directors (“Board”), and regulators.

Next let dive deeper into each step of the cycle:

Identification

To ensure a comprehensive view, the Board and senior management must actively recognize top and material risks that are inherent to the business - as well as emerging risks. Emerging risks are not yet fully understood and are associated with e.g.: changing technology, regulations, and consumer sentiment. For large and more complex FSOs, this process must also include identification of concentration risks, e.g.: narrow funding sources, substantial proportion of revenue originating from the same set of clients, or critical third-party dependencies. Significant organizational changes, e.g.: mergers, acquisitions, and consolidations should trigger a comprehensive risk identification exercise to navigate the change.

Risk identification draws on both internal and external sources to catalogue all risks facing the enterprise. Internally, primary sources include detailed process mapping, risk event data, issue management data, management information and reports, and insights gathered through workshops with subject matter experts (SMEs). Externally, critical sources are regulatory and legislative changes, geopolitical shifts, macroeconomic trends, and competitor actions. Furthermore, structured data from industry loss consortia and external audit findings provide valuable benchmarks and insight into emerging or systemic risks that may be overlooked internally. The combination of these sources ensures a holistic and timely view of potential threats.

Risk identification is not only an enterprise-level discipline and is applicable at every level of the organization, down to understanding where risks are in a process or individual project. At the enterprise-level, risk management seeks to understand exposures that could impact the FSO’s strategic objectives. Yet this enterprise view is only as strong as its foundation - the identification of risks at the process and business-unit level. These micro-level insights are aggregated upward to create a holistic picture of the firm’s risk profile, demonstrating that while risk identification occurs at multiple levels, the process is inherently integrated and mutually reinforcing.

Risk identification is the basis for risk response. If you don’t identify it - you can’t manage it.

Identification of rate and liquidity exposure in the 2023 banking crisis

A compelling real-world example involves interest rate risk and liquidity risk at many U.S. banks in early 2023, both of which were readily identifiable through regular risk monitoring and regulatory reports.

From 2020 to early 2022, many banks invested trillions of dollars of pandemic-era deposit growth into long-term bonds (like U.S. Treasuries) when interest rates were near zero. When the Federal Reserve Bank rapidly raised interest rates in 2022, the market value of those long-term bonds plummeted, creating huge unrealized losses on the banks’ balance sheets.

These same banks often had a high concentration of uninsured deposits (deposits over the $250,000 FDIC limit), particularly from tech companies or large corporate clients, making them more sensitive and prone to flight-to-safety.

Through routine risk analysis and stress testing, many banks clearly identified that a sizable portion of their bond portfolio was underwater (suffering unrealized losses). Regulators and risk management had been warning the financial sector about the duration mismatch (holding long-term assets funded by short-term deposits).

While some prominent FSO failed, many others successfully identified and acted on the risks, preventing similar collapse. The risk response involved immediately shoring up liquidity by tapping lending facilities, diversifying their funding to reduce the concentration of flight risk, and sold certain underwater bond holdings (realizing losses).

Measurement

Accurate and timely measurement of risks is an essential prerequisite for understanding risk levels before deploying an appropriate risk response. By effectively measuring risk exposure it becomes possible to assess identified risks and then risk rate them - to determine priority of action in line with Board-approved risk appetite. Risk measurement tools must be appropriate to fully capture the risk exposure and include the use of models. It is important to note the measurements should be deployed at various levels of fidelity, mirroring risk identification across different levels of the enterprise.

For any identified risk, it is prudent to establish multiple complementary risk measures rather than relying on a single measure. Overdependence on one measure can create blind spots and a false sense of security, as no single metric can capture the full complexity or nuance of real-world conditions. A balanced set of measurements provides a more reliable and holistic view of the underlying risk.

Conducting periodic tests to verify the accuracy and reliability of these measurements is necessary on an ongoing basis. Finally, significant organizational changes e.g.: mergers, acquisitions, and consolidations should trigger a review of risk measurements to ensure risk exposures are appropriately assessed.

Understanding what to measure is far more critical than simply having a number.

When overreliance on a single model obscures the real risk

This real-world example highlights the need for appropriate measurement of risk exposure. The Chief Investment Office (CIO) of a large bank held a complex derivatives portfolio, for macro hedging purposes. The bank relied primarily on a risk metric called Value-at-Risk (VaR) to measure the exposure of this portfolio.

VaR is a statistical measure that estimates the maximum amount a portfolio is likely to lose over a set period (e.g., one day) with a certain degree of confidence (e.g., 99%). The crucial flaw was that the bank’s VaR model was based on historical data and correlation assumptions that were not in keeping with the real risk exposure. It furthermore included various calculation errors that were due to manual entries.

This resulted in the model consistently producing an artificially low VaR number, indicating that the portfolio risk was small and within limits. In reality, the true exposure (measured by the actual potential loss in extreme market conditions) was excessive.

The failure to use comprehensive measurements ultimately cost the bank over $6.2BN once market conditions deteriorated and the positions had to be unwound. The bank failed to emphasize stress testing and maximum potential loss metrics, which would have revealed the true outlier event risk. Understanding what to measure is far more critical than simply having a number, as an inaccurate or incomplete metric can mask the true risk exposure with very costly consequences.

Monitoring

Risk monitoring is a continuous process of scanning the business environment and detecting where risk levels are becoming too large (small). One such formal process is the periodic assessment of the FSO’s risk profile against the Board-approved risk appetite. Here risk indicators and metrics are reviewed across all risk categories and assessed against established thresholds and limits to determine whether or not there are any breaches. Any breaches must then be escalated all the way up to the Enterprise Risk Management Committee (ERMC) (or equivalent - most senior risk committee at the management level), which may apply a degree of qualitative overlay of the breach(es) to determine whether the FSO is in or out of risk appetite for a given risk category. Other FSOs may simply treat a breach to mean that it is out of appetite - without a management-level overlay. I have seen both work well. What is less contentious is that the ERMC will oversee corrective actions to bring the FSO within risk appetite.

In sophisticated FSOs, a lot of risk monitoring is automated and centralized on a digital platform with close-to real-time feeds providing management with a timely view of how risk exposure is changing. Less sophisticated FSOs will rely on Excel and PowerPoint (or equivalent). In any case; establishing how Management Information (MI) is to be disseminated (which risk management committee sees what - including the Board), how frequently, via what channel (report or e.g.: digital dashboard), and with what purpose (for awareness or for action) are all critical elements of effective risk governance.

Accurate and complete data is paramount for effective risk monitoring in an FSO, as the ability to reliably detect and pinpoint critical deviations in the risk exposure wholly dependent upon the integrity and timeliness of the underlying data and reporting infrastructure.

Over time management will be able to effectively determine which metrics provide value-adding insight into the risk environment and which ones are less useful. In other words, monitoring is a dynamic routine, which will need to adapt to what management want to see, the business strategy, evolving technology and other external forces. This is more of an art. Thresholds and limits also need to be periodically recalibrated and back-tested - ideally using data from periods of normal operations and periods of stress.

When a threshold or limit is breached, it is essential not to second-guess the rationale that guided its original design. Dismissing a breach as a one-off exception undermines the integrity of risk governance. Instead, follow the established escalation process to determine whether management action or control remediation is warranted.

Monitoring cyber risk exposure

This example focuses on Cybersecurity Risk and Operational Risk within a large commercial bank, which sought to avoid a data breach.

Risk management identified that a critical risk was the failure to patch vulnerabilities in its vast network of software, which could lead to a system intrusion and loss of sensitive and confidential data, including Personally Identifiable Information (PII). Such a risk would lead to added regulatory scrutiny (and potential penalties), severe customer and reputational harm, and financial impact through added expenses to remediate technology issues and compensate impacted customers and stakeholders.

The technology risk team established an indicator to determine the average time to patch critical vulnerabilities and set an early warning threshold of 3 days and a hard limit of 7 days. Technology was implemented to scan the network daily, calculate the time a critical vulnerability had been exposed, and feed the data into a centralized risk dashboard.

For several months, business-as-usual (BAU) ran smoothly, with the indicator hovering around 2.5 days. The FSO was operating well within its defined threshold. However, in late November the monitoring system detected an unusual spike: the average time it took to patch critical vulnerability jumped to 6 days - triggering an early warning. This triggered an automatic alert to senior business and risk leaders.

The operational risk manager investigated and found that the Technology team was unexpectedly understaffed due to a wave of sickness and they were struggling to keep up with a high volume of new, complex vulnerabilities.

When the following week, the average time jumped up to 8 days, a formal escalation was triggered to the Chief Risk Officer (CRO) and Chief Information Officer (CIO), who immediately requested that the Technology team engage a technology consultancy, to help patch all critical vulnerabilities within 48 hours.

Through rigorous monitoring and appropriate timely actions, the FSO was able to avoid a cyber event, but at the cost of engaging and on-boarding consultants to support operations.

Response

Risk response is arguably the most critical phase as it translates understanding the environment into judgement and action. The fundamental importance of this stage lies in ensuring that risks are not merely identified, but actively treated to avoid jeopardizing the FSO’s stability and long-term viability. Every risk response reflects a deeper decision about the FSO’s appetite for uncertainty, its confidence in its internal control environment, and its willingness to manage the inherent risks of doing business. This is where real leadership comes into play - requiring a strategic mindset, some imagination, the humility to seek out and rely on subject matter expertise, and the ability to ask the incisive questions that inform critical decisions.

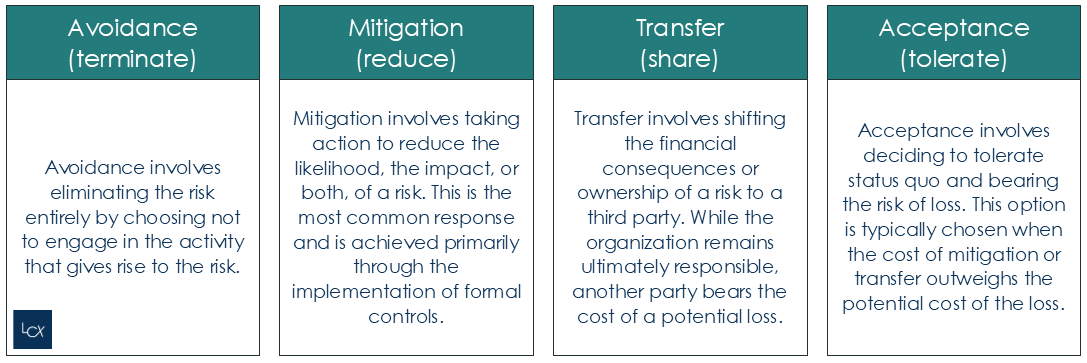

Risk response typically has four fundamental responses - see figure 2:

Deploying a risk response is not a reactive exercise triggered by a market shock or adverse event. It is an ongoing risk routine that must be executed at every layer of the FSO. The need to identify, scrutinize, and adjust responses is constant - whether at the operational, tactical or strategic level. This is, in many ways, the most difficult stage of the RMLC, because it relies on judgement, subjectivity, and business acumen.

That being said, there are formal risk routines that are quite structured, repeatable, and effective in mitigating risks. These routines include:

The Risk and Control Self-Assessment (RCSA), which is a formal risk program that seeks to understand the end-to-end business process, identify risks within that process and design and execute controls to reduce the likelihood and impact from these risks.

Clear thresholds and limit setting across the organization, including the necessary protocols for authorizing and managing exceptions.

Furthermore, Internal Audit provides independent and objective assurance to the Board and senior management regarding the design adequacy and operating effectiveness of the internal control environment and the overall governance structure, thereby confirming the integrity of the firm’s risk posture.

Now that risk reduction has been deployed - assess the residual risk to determine whether appropriate risk mitigation has been achieved.

External data failure and trading frenzy

This example demonstrates how a well-designed internal control was able to prevent huge losses.

A technical error on an exchange was flooding a routine market feed with dummy data. An FSO relied on this particular feed for its index product, which was now being fed extremely high and low price quotes that did not reflect the actual market value.

The FSO’s high-frequency trading algorithms, designed to react to arbitrage opportunities, immediately interpreted this volatile data as a major market event, and began generating large trade orders based on the erroneous data.

The size of these orders exposed the FSO to severe losses and market risk. Not only would these trades result in immediate, unrecoverable losses for the FSO, but they also carried the risk of destabilizing the wider market.

However, the FSO had implemented a price collar control, which was designed to compare the calculated trading price against a preset maximum deviation limit from the last known good price. Since these trades exceeded that limit, the trades were automatically rejected. This essential control worked as intended - resulting in a near miss (meaning a risk event was narrowly avoided) and preventing financial, reputational, and regulatory calamity. It was all over before it became clear what had happened.

Report

The final stage in the RMLC is risk reporting, which serves as the primary mechanism for governance and oversight. Effective reporting is essential for validating that the FSO operates within Board-approved risk appetite and enables the Board and senior management to make informed risk decisions. The FSO must be capable of aggregating risks across the entire enterprise in a timely manner. Other data elements such as issues, risk events, incidents, corrective actions, policy violations, (and many more than I can list here), are all essential in providing a holistic view of the FSO’s health. The information in these reports must adhere to five key principles:

Completeness - covering all material risks and exposures.

Accuracy - ensuring data is free from error.

Timeliness - occurring on a frequency where it can be acted upon.

Consistency - using standardized metrics and formats across the enterprise.

Relevance - presenting pertinent information at an appropriate level of detail.

Robust risk reporting is fundamentally dependent on effective data architecture and robust data governance and risk taxonomy. This dedicated architecture must have the ability to capture and aggregate data and report material risks, concentrations, and emerging risks in a timely manner to senior management, the Board, and regulators. Like the other phases, reporting is necessary at all distinct levels of the organizations to serve distinct objectives. As such, the data must be scalable to show aggregate as well as detailed views depending on the needs. At the bottom of the organization, data needs will typically be narrow in scope (to a team or function) and high in detail. Whereas at top of the organization, e.g.: the Board, data needs will typically be broad in scope (enterprise wide) and aggregate in nature. Both are essential.

The repurchase (“Repo”) scheme.

This example highlights how deliberate manipulation of risk reporting resulted in failure.

An FSO exploited a loophole in accounting standards - executing a Repo transaction to mask an overleveraged position. This scheme involved temporarily moving assets off the balance sheet shortly before the reporting cut-off period. The FSO would sell risky securities under Repo contracts but classify the transaction as a true sale rather than a collateralized loan.

The FSO was able to reduce its reported liabilities (debt) and its net leverage ratio for a few days around the end of each quarter. Meanwhile the FSO officially released reports and financial statements without fully disclosing the extent of their debt and leverage.

Then a severe market downturn hit - drying up the otherwise liquid credit market. The system came to a halt - effectively eliminating the FSO’s ability to execute their typical repo trades. FSOs could no longer meet their short-term borrowing needs, which made them very vulnerable to any outflows. Management was ultimately forced to disclose the true, extreme level of debt and the lack of high-quality liquid assets to cover immediate obligations. This sparked an immediate breakdown in trust further exacerbating the problem. As a result, the FSO went under sparking market contagion.

The Repo scheme is a powerful example of how a deliberate manipulation in completeness, accuracy and transparency of financial and risk reporting can fatally undermine market confidence and contribute to a catastrophic event.

Conclusion

The RMLC is not a one-time exercise but a continuous, cyclical process that, when integrated with robust risk governance, enables an FSO to proactively manage risk in line with its risk appetite. Conversely, some of the real-life examples that I covered starkly illustrate how breakdowns at any point in the cycle can result in catastrophic and undesirable consequences.

Ultimately, good execution turns the RMLC into a flywheel: every iteration enhances institutional learning, sharpens risk awareness, and strengthens the FSO’s capacity to adapt and grow responsibly.